Research Articles

ECMO Machine May Improve Survival for Some COVID-19 Patients

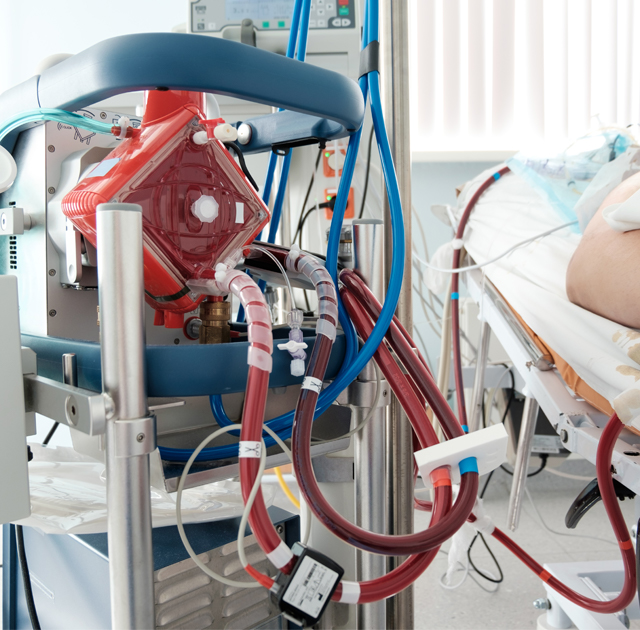

ECMO life support machine being used to treat COVID-19 patients.

ECMO life support machine being used to treat COVID-19 patients.Study provides some clinical guidance on its efficacy.

UH College of Medicine Researchers Study Best Practices for ECMO with COVID-19

By India Ogazi

July 31, 2020

On April 16, 2020, Chicago’s CBS news station reported that a critically ill COVID-19 patient had recovered from the deadly virus with the help of a heart-lung machine called ECMO. Yet, like so many COVID-19 supportive strategies, its feasibility and best practices for COVID-19 patients is unclear. University of Houston College of Medicine’s Drs. Faisal Cheema and Keshava Rajagopal are working to change that.

At the beginning of the pandemic, ventilators were the high-demand, life-support device. However, in a search for more effective recovery strategies, the ECMO is being used for critically ill patients, as well.

Along with researchers from West Virginia University, Cheema and Rajagopal analyzed the clinical experience of 32 COVID-19 patients with severe lung damage who were supported with ECMO.

Their report was published in the July issue of ASAIO Journal — the official publication of the American Society for Artificial Internal Organs. This report complements their June ASAIO publication that provides clinical guidance on ECMO, and other artificial lung and heart support use, in COVID-19.

ECMO, the extracorporeal membrane oxygenation machine, is used in critical care patients whose heart and or lungs are badly damaged and need to rest and heal. The patient’s blood is pumped into the ECMO, which functions as the heart and lungs as it removes the carbon dioxide from the blood, fills it with oxygen and pumps it back into the body. As there is no cure for COVID-19, the body has to heal itself from the havoc it racks on its organs. ECMO helps that to happen.

The researchers studied data of patients who were on ECMO over a 24-day period.

At the time of the analysis’ completion, of the 32 patients, 17 remained on ECMO, 10 died and five were alive and removed from ECMO. The five successfully removed from the life-support machine all received a kind of ECMO that supports the lungs but not the heart. In contrast, at the time of the paper’s publication, none of the patients who had lung and heart ECMO support had been removed from ECMO.

“Based on the current analysis, the data suggests that COVID-19 lung failure patients do much better on ECMO than severe cardiac failure patients,” said Rajagopal. This data is consistent with previous ECMO research regarding its use with lung failure and severe cardiac patients, he added.

However, Rajagopal quickly stresses that this doesn’t mean ECMO shouldn’t be used on patients with severe cardiac failure because there is often no other alternative for these patients. “Poor outcomes are still better than guaranteed death,” he said.

The study also showed that patients who were under 65 with fewer preexisting conditions also had better outcomes on ECMO than older patients with underlying health issues.

“If a hospital has a limited ECMO supply, this gives guidance as to who would be the best candidate for receiving this therapy,” Rajagopal explained.

The researchers stress that the report contains very preliminary data and additional follow-up is required on all surviving patients. Yet, currently, it provides health care practitioners more clear guidance on using ECMO for saving the most critically ill COVID-19 patients.