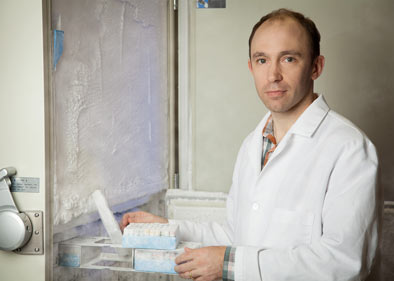

Going back in time to compare evolutionary changes in several thousand generations

of E. coli, a University of Houston (UH) biologist hopes to one day be able to isolate

a bacterial pathogen and predict the likelihood it will become resistant to a particular

antibiotic.

“Evolvability is when biological populations have the capacity to adapt to changing

conditions,” Cooper said. “By studying how generations of bacteria evolve over time,

we are learning ways to predict the outcome of the changes and to understand what

drives the differences in the way strains of bacteria evolve. We hope this type of

evolutionary biology research will impact medical care by contributing to the ability

to predict the evolutionary paths of bacterial populations.”

Evolvability plays a crucial role in determining evolutionary winners and losers among

the many variants that arise in any bacterial population in that they are either improved

or become extinct. Through his research, Cooper wants to gain the ability to predict

these winners and losers, because this knowledge gives an element of predictability

to evolution. This would predict such things as antibiotic resistance.

Cooper’s evolvability research with the E. coli began two years ago with the first

petri dish of this fast-growing bacteria. He says they are lucky, because the experiments

are incredibly simple. His team grew the initial bacteria in a petri dish and took

a sample to grow in a test tube with fresh media. That process continued day after

day with the bacterial populations growing and a sample being taken from each test

tube culture. Cooper now has a set of experimental populations that have evolved for

more than 7,000 generations.

“This simplicity is deliberate, so that we can track back what has happened to the

strain,” Cooper said. “Every 500 generations, which is about every two months, we

freeze a sample of each evolving population to create a living fossil record. Because

the frozen samples are revivable, we can compare a past population with its future

population.”

“At this point, we predict an average of about 15 genetic changes to have occurred

in each population evolved for the 7,000 generations,” Cooper said. “Though that number

may seem small, it’s sufficient enough to increase the bacteria’s growth rate by up

to 50 percent.”

Cooper became interested in studying evolvability because it is a long-standing question

in evolutionary biology as something that can be modeled in most natural populations,

but not measured. While it’s clear from computational models that evolvability can

have a major impact on how evolution unfolds, direct study of the phenomenon is required

to assess just how big an impact it does have. His group’s experimental system with

fast-evolving bacterial populations allows them to design experiments that can look

at it directly.

###

About the University of Houston

The University of Houston is a Carnegie-designated Tier One public research university

recognized by The Princeton Review as one of the nation’s best colleges for undergraduate

education. UH serves the globally competitive Houston and Gulf Coast Region by providing

world-class faculty, experiential learning and strategic industry partnerships. Located

in the nation’s fourth-largest city, UH serves more than 39,500 students in the most

ethnically and culturally diverse region in the country. For more information about

UH, visit the university’s newsroom.

About the College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics

The UH College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, with 193 ranked faculty and nearly

6,000 students, offers bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees in the natural sciences,

computational sciences and mathematics. Faculty members in the departments of biology

and biochemistry, chemistry, computer science, earth and atmospheric sciences, mathematics

and physics conduct internationally recognized research in collaboration with industry,

Texas Medical Center institutions, NASA and others worldwide.

To receive UH science news via email, sign up for UH-SciNews.

For additional news alerts about UH, follow us on Facebook and Twitter.