The Houston Negro Hospital (1900-1926, Section 9)

It quickly became apparent, however, that Union-Jeremiah Hospital could not meet the needs of Houston’s growing black community. Led by their physicians, the community began to explore construction of a new hospital. Impressed by the efforts of Union Hospital’s five founders, oilman Joseph Cullinan contributed $80,000 to help build a new and larger hospital. The city of Houston donated three acres of land and the building soon rose up at Elgin and Ennis streets in the Third Ward.

1926

On June 19, 1926, Mr. Cullinan dedicated the cornerstone for the new hospital to the black community and in memory of his son John, who died shortly after his military service in World War I. As an army officer, John Cullinan led black soldiers, and his favorable impression of their service influenced his father’s decision to offer financial support. The bronze tablet posted on the front of the building read,

“This building erected A.D. 1926, in memory of Lieutenant John Halm Cullinan, 334th F. A. 90th Division, A. E. F., one of the millions of young Americans who served in the World War to preserve and perpetuate human liberty without regard to race, creed, or color, is dedicated to the American Negro to promote self-help, to inspire good citizenship and for the relief of suffering sickness and disease amongst them.”

Isaiah Milligan (I.M.) Terrell had retired the presidency of Houston College in 1925 to help raise funds for this new hospital. In the late 1800s, he had helped organize Prairie View A&M University for African-American students some 40 miles northwest of Houston. Named the hospital’s first superintendent, Professor Terrell expressed the gratitude of the African-American community at the dedication in 1926 and predicted that services the hospital would provide “would spread throughout the country,” inspiring others to, “erect similar buildings for the alleviation of human suffering.” 1

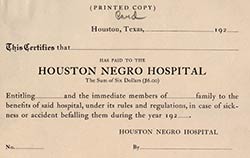

Prepaid Health Care

The Houston Negro Hospital, which was later known as Riverside General Hospital, opened to patients on May 14, 1927. In a type of prepaid system that appeared in other facilities as well, the Houston Negro Hospital sold families memberships for $6 a year. These memberships guaranteed all family members were eligible for free hospitalization for a limited number of days each year. While such memberships were not a prerequisite for care and thus all African Americans were welcome at the hospital, this prepaid system helped underwrite hospital operations.

In addition to providing a much-needed facility for black patients, the Houston Negro Hospital gave African-American physicians a place to work. In creating entities such as the Houston Negro Hospital and the National Medical Association, “black professionals identified the Achilles" heel of white supremacy. Segregation provided blacks the chance, indeed, the imperative, to develop a range of distinct institutions that they controlled. Maneuvering through their organizations and institutions, they exploited that fundamental weakness in the ‘separate but equal’ system permitted by the U.S. Supreme Court's 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson. For all their violence, lynchings, prejudice, and hatred, white supremacists could not exterminate black people. The white supremacists’ major goal, after all, was to maintain a pliable, exploitable labor force that would remain permanently in a subordinate place.”

Their education separated black professionals from other members of the African-American community and allowed them to emerge as community leaders. Parallel institutions, such as the Houston Negro Hospital, provided relatively safe havens for African-American physicians to hone their skills, nurture professional relations, and develop financial security. Black doctors tended to be more financially secure than black attorneys, for example, who worked within the country’s singular legal system. Nonetheless, both groups used parallel professional organizations such as the Lone Star Medical Association to forge innovative strategies for resistance. 2