The Medical Profession at the Turn of the Century (1900-1926, Section 2)

Jim Crow Laws and Segregation

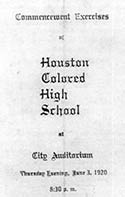

As Dr. Robey and other Houstonians entered the twentieth century, they lived in a nation that had yet to deliver on its promise of equality for all. The decades following the Civil War led to the enactment of Jim Crow laws by 21 states, including all southern states. In other parts of the country, African Americans faced de facto segregation. To combat discrimination and to protect and promote their rights, African Americans formed organizations, such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909. They also built colleges, medical schools, and other training institutions, believing that education would elevate their communities.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, for both blacks and whites, professional training did not always include college. Many people received on-the-job training as apprentices in professions such as medicine; others simply claimed the title “healer.” While some physicians attended medical school, no system existed to certify the quality of American medical schools. Most schools only offered two-year programs. More ambitious medical students, who could afford to do so, traveled to Europe for additional studies.

At the same time, as more Americans and immigrants flooded the nation’s booming industrial cities, there were new concerns about the crowded and unsanitary conditions they encountered. Such conditions contributed to epidemics and other ongoing health problems. In many cities, infant mortality rates were extremely high. In Chicago in 1900, for example, 125 of every 1000 infants died in the first year of life. Some Progressive Era reformers , hoping to alleviate various health problems, focused on underlying problems with the physical infrastructure, trying to improve systems for supplying water or treating sewage.

Others believed the solutions lay in enhancing medical care by preventing “anyone with a bag of pills” from acting as a medical professional. 1 To do so, they worked to strengthen vague licensing laws that allowed many individuals to claim the title of healer regardless of their limited qualifications. Physicians who had trained in the nation’s medical schools also banded together to limit the activities of a growing corps of poorly trained healers and to eliminate potential competitors. Founded in 1847, the American Medical Association (AMA) and other regional medical organizations began lobbying in the early 1900s for stricter licensing laws that defined the education required of future doctors.

The majority of African-American physicians did not join the AMA because entry depended upon membership in a physician’s county and state association, and most local associations denied admission to black doctors during much of the twentieth century. Dr. Edith Irby Jones recounts the situation before the mid-1950s: “You [had] to be a member of the local society, and . . . of the state society, but if the local society won’t accept you, then you can’t be a member of the state or national organization. So, it was a Catch 22.” 2

In response to this discrimination and to promote the art and science of medicine in their own ranks, groups of black doctors formed their own local medical societies. In Texas, the Lone Star Medical Association held its first meeting in Galveston in 1886 and began to represent the state’s black physicians. Nationally, African-American physicians formed the National Medical Association (NMA) in 1895 to promote their interests and to protect and improve the health of African Americans across the entire country.

Citations

- Robert H. Wiebe, Search for Order, 1877-1920 (New York: Hill and Wang, 1967)

- Dr. Edith Irby Jones, Interview by Leigh Cutler, Lauren Kerr, and Yimei Zhang, March 10, 2005, tape recording.