Khan Receives Grant to Study Pakistan’s Chaman Fault

Study will Enhance Earthquake Prediction and Mitigation in Region

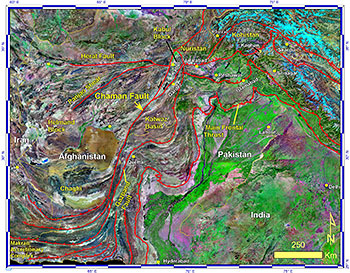

Sketch map of southeast Asia showing major faults and tectonic blocks, including the Chaman Fault.

Related Links:

• KUHF Interview

• Daily CougarA three-year, $451,000 grant from the United States Agency for International Development to study the Chaman Fault in Western Pakistan will help earthquake prediction and mitigation in this heavily populated region.

The research, part of the Pakistan-U.S. Science and Technology Cooperation Program, will also increase the strength and breadth of cooperation and linkages between Pakistani scientists and institutions with counterparts in the U.S. The National Academy of Sciences implements the U.S. side of the program.

Shuhab Khan, associate professor of geology at University of Houston, will lead the project in the U.S. His counterpart in Pakistan is Abdul Salam Khan of the University of Balochistan.

“The Chaman Fault is a large, active fault around 1,000 kilometers, or 620 miles, long. It crosses back and forth between Afghanistan and Pakistan, ultimately merging with some other faults and going to the Arabian Sea,” Khan said.

The study area is located close to megacities in both countries.

“Seismic activity across this region has caused hundreds of thousands of deaths and catastrophic economic losses,” Khan said. “However, the Chaman Fault is one of the least studied fault systems. Through this research, we will determine how fast the fault is moving and which part is more active.”

The Chaman Fault is the largest, strike-slip fault system in Central Asia. It is a little more than half the size of the San Andreas Fault in California.

“In strike-slip faults, the Earth’s crust moves laterally. Earthquakes along these types of faults are shallow and more damaging,” he said. “Rivers can also be displaced and change course with activity related to this type of fault.”

The study team will gather data using remote sensing satellite technology and field measurements made at various sites along the fault.

“In addition to current movement, the techniques will allow us to go back tens of thousands of years to determine which areas have moved and how much,” Khan said.

Field measurement techniques include sampling and analysis of rocks and sand along the fault system.

“Through cosmogenic age dating, we can determine how much time rocks along the fault have been exposed to sunlight by measuring for cosmic rays and radiation. Those measurements help us determine how much time it took the rocks to move in the area,” Khan said.

Sand buried below the surface will be sampled without being exposed to light. In the lab, measurements using optically stimulated luminescence will reveal how long the sand has been buried.

Three students from the University of Balochistan will come to the U.S. to learn the field techniques. “We will take them to the San Andreas Fault for training because the locations and faults are similar,” Khan said. “They will return to Pakistan and gather samples from designated areas along the fault.”

The samples will be analyzed at the University of Cincinnati lab of geology professor Lewis Owen, co-investigator on the grant. The research team also includes University of Houston geosciences students. Two undergraduate students will help process the rock samples, and a Ph.D. student will work with the remote sensing data.

“Through the data collection, we will learn more about the movement along this fault in the recent past. That information will help with earthquake prediction and mitigation,” Khan said.

- Kathy Major, College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics