A University of Houston researcher has earned a $1.8 million grant from the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative to determine how the use of dispersants to break up an oil spill affects the natural cleaning role played by bacteria.

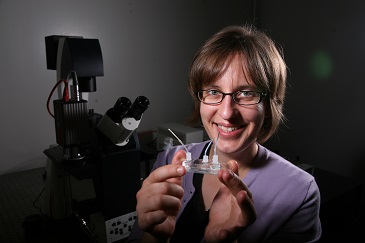

Jacinta Conrad, assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering, said the work will answer fundamental questions important to understanding how bacteria – microscale organisms that naturally occur in marine environments – can help in cleaning up spills during offshore drilling and production.

The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative was formed in 2010 after BP’s Deepwater Horizon drilling rig exploded about 50 miles off the coast of Louisiana, killing 11 men and spilling several million barrels of oil in the five months before the well was sealed. BP pledged $500 million over 10 years for an independent research program to study how the spill and efforts to clean it up have affected the Gulf and coastal states.

The initiative is seeking answers in several areas, including the environmental impact of the oil and dispersants, the public health impacts and the development of new technology to use in future spills.

Conrad’s project builds on her previous work in colloid and interfacial science – the study of how complex fluids move, including the movement of bacteria across surfaces. For this project, she will lead a team of three investigators: Roseanne Ford from the University of Virginia; Arezoo Ardekani from Purdue University, and Douglas Bartlett from the University of California-San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

Crews attempting to limit damage caused by oil spilled from the Deepwater Horizon used chemical dispersants – chemicals sprayed onto a surface oil slick – to break the oil into smaller droplets. Preliminary studies have questioned whether the dispersant worked the way it was intended.

But there also is a natural remedy for oil spills – hydrocarbons are a source of food for various strains of bacteria in the water, and Conrad and her team will look at whether the dispersants affected the movement of these bacteria toward the spilled oil.

“An oil spill in the ocean is a big, glowing beacon of food to bacteria,” she said. “Our work will test whether dispersants changed the rate at which bacteria moved towards the oil and the rate at which they consumed it.

“The really critical question we are asking is how human intervention – the dispersants – interacts with natural cleaning processes – the bacteria,” she said. “If dispersants lowered the rate at which bacteria removed the oil, then human efforts to clean up the spill may have been costly and counter-productive.”

Her ultimate goal is to determine whether the dispersants helped draw bacteria to the oil and, if so, to measure the impact.

“We expect that better understanding of how dispersants affect bacterial biodegradation processes will inform future strategies to clean spilled oil,” she said.