The familiar murkiness of waters in the Gulf of Mexico can be off-putting for beachgoers visiting Galveston Island. Runoff from the Mississippi River makes its way to local beaches and causes downstream water to turn opaque and brown. Mud is one factor, and river runoff is another. However, concern tends to ratchet up a notch when pollution enters the river runoff discussion on a national scale, specifically when smaller, navigable intrastate bodies of water push pollution into larger interstate waters often involved in commerce (i.e. the Mississippi River, Great Lakes, Ohio River).

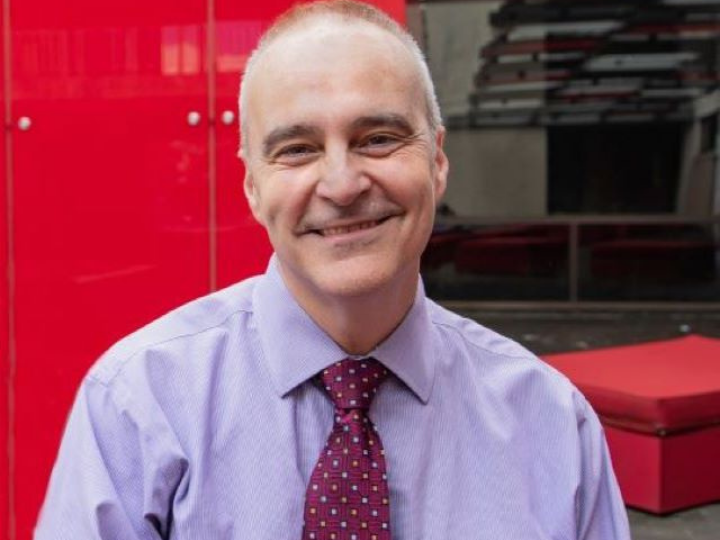

A recently published research analysis in the journal Science, co-authored by Victor Flatt, Dwight Olds Chair in Law at the University of Houston Law Center, demonstrates how the supposed benefits of retracting federal oversight on these transboundary waters and defaulting that responsibility to individual states failed to account for economic and scientific evidence that said otherwise and violated the bounds of justifiable law.

In the article, “A water rule that turns a blind eye to transboundary pollution,” Flatt contributed as the sole legal researcher, explaining how the 2020 Navigable Waters Protection Rule, which retracted federal oversight of interstate waters, did so with the overt assumption that state governments would fill in the oversight gap. Not only did the evidence point toward an alternate outcome but the rule’s federalism rationale was incorrect, according to the researchers.

“New administrations get to implement new policies, but those policies have to be consistent with statutes, the Constitution and be logical,” Flatt said. “The legal phrase is: ‘they cannot be arbitrary and capricious.’ An administration can only do what is allowed by the law and must be rational and logical. This fails that. This is a policy disagreement, but it is a policy disagreement that is out of the bounds of what is allowed by law.”

The cleanliness of larger transboundary rivers falls under the responsibility of the federal government and under the 2015 Clean Water Rule (CWR) enacted during former President Barack Obama’s administration. This included small wetlands and streams that could push pollution runoff to these larger rivers that bisect several states. In 2020, under the Navigable Waters Protection Rule (NWPR), the federal regulation of some of those smaller, linked bodies of water was withdrawn, leaving individual states with the responsibility to fill in the gaps. However, many states did not assert control over these waters as assumed by former President Donald Trump’s administration, leaving room for pollution to make its way to interstate waters.

“One prominent example is 31 states’ challenge to the 2015 CWR in court, arguing that it would impose excessive costs. Inexplicably, the NWPR’s economics analysis projected that 14 of these states would now change their position,” according to the Science article. As Flatt explains, this assumption was the misstep.

“The Army Corps and EPA said in their analysis that 31 states will move into the breach and help protect the wetlands that the federal government would no longer protect,” Flatt said. “But best practices for economic analysis state that you cannot speculate about future state actions. When I looked at this, I found a lot of these states are even prohibited from enacting a rule more stringent than the federal government. Here, the data is flawed.”

In March, President Joe Biden’s administration proposed a $111 billion investment in water infrastructure. Flatt said that the implementation of the investment will include review of previous policy and research, including information uncovered in the Science article.

Research to inform this article was funded by the External Environmental Economics Advisory Committee, with funding and support from the UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation and Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

Co-authors for the paper include Sheila Olmstead, professor of public affairs at the University of Texas at Austin; David Keiser, associate professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst; Kevin Boyle, professor of agriculture and applied economics at Virginia Tech; Bonnie Keeler, assistant professor at the school of public affairs at the University of Minnesota; Catherin Kling, Tisch University Professor at the school of applied economics and management at Cornell University; Daniel Phaneuf, Henry C. Taylor Professor and Chair of agricultural and applied economics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison; Joseph Shapiro, associate professor at the University of California, Berkley and Jay Shimshack, associate dean and associate professor of public policy and economics at the University of Virginia.