While to most people coins may seem like mere common currency, to a numismatist they are a window to the past. Associate Professor of History, Dr. Kristina Neumann uses her new book to critically assess how viewing the coins of ancient Antioch can illuminate their society and economy.

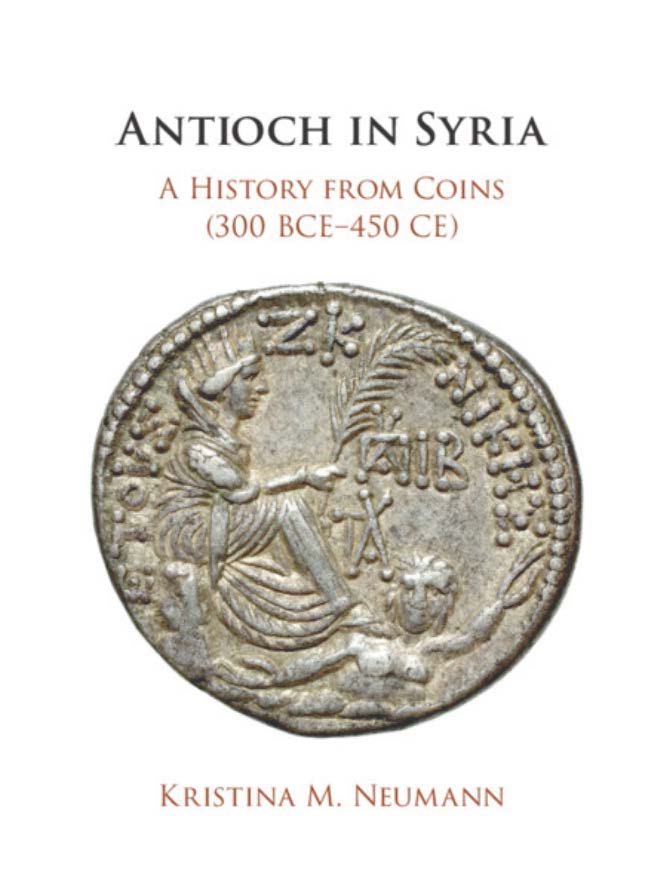

Neumann’s book, Antioch in Syria: a history from coins (300 BCE-450 CE), recently received praise in a review from Bryn Mawr Classical Review for using coins as a primary source for adding to the understanding the history of Antioch.

The Bryn Mawr Classical Review began at Bryn Mawr College in 1990 and is the second oldest online scholarly journal in the humanities. BMCR is dedicated to providing objective and fair peer review for works related to the classical world.

The review by Alan Stahl, Curator of Numismatics at Princeton University, reveals that while there have been other publications related to the history of Antioch, Neumann’s work reveals how the ancient Antiochians used coin iconography and coin inscriptions to reflect their self-image.

The coins themselves are classified by Neumann into three separate categories: imperial coinage, civic coinage, provincial coinage. While using this classification system, the book moves through chronological periods to determine the minting and usage of the various kinds of coins.

In the earliest period examined her book, Neumann views the differences in imperial coinage of the Seleucid period to that of civic coins. While imperial coins bore the name of kings and the territory they controlled, the bronze civic coins replace the royal name with the legend “of the Antiochians” and thus elevate the citizens to the level of a true Greek polis.

As Seleucid rule eroded near the end of the first century BCE and Rome asserted more influence and control of the Syrian region through the first century CE, Neumann’s research demonstrates an increase in the number of coins issued in the name of the Antiochians. In a period fraught with questions of legitimate political and money-minting authority, Neumann sees the Antiochians uniquely asserting their own civic identity—through coin inscriptions and imagery—as a recognizable, trustworthy minting power, possibly to maintain the stability of low-denomination coinage in the face of governmental turmoil.

In her coverage of the later, Roman-dominated centuries, Stahl notes Neumann’s inclusion of helpful detailed coin distribution maps and charts. These visual resources not only show the broad distribution patterns for Antioch coins into the third century CE, but her charts and maps of coins have provided a unique key for seeing a greater level of integration (rather than decay) across the diverse Mediterranean cultures than previously thought.

Overall, Stahl praises Neumann’s book for her use of original and secondary sources, as well as making her maps and charts available on an open access website: https://syrios.uh.edu.

Far from being a book limited only to the city of ancient Antioch, Stahl writes:“Kristina Neumann’s use of coinage as a lens to view the civic identity of Antioch and its citizens across seven-and-a-half centuries of its history provides significant new insights into the structures and processes of the ancient Mediterranean world as a whole.”