With seemingly endless emails, phone calls and meetings, it’s no secret that working in an office environment can be quite stressful. Understanding how stress manifests by exposing the effects of distractions can help unlock an office workers’ full potential, according to new data collected by researchers from three university laboratories.

Ioannis Pavlidis, director of the Computational Physiology Laboratory at the University of Houston, along with Ricardo Gutierrez-Osuna from Texas A&M University and Gloria Mark from the University of California Irvine, conducted an experiment using thermal imaging and wearable sensors to better understand the stress and performance patterns of so-called knowledge workers – scientists, engineers, designers and academics. The findings are published in the journal Scientific Data.

Preliminary observations include:

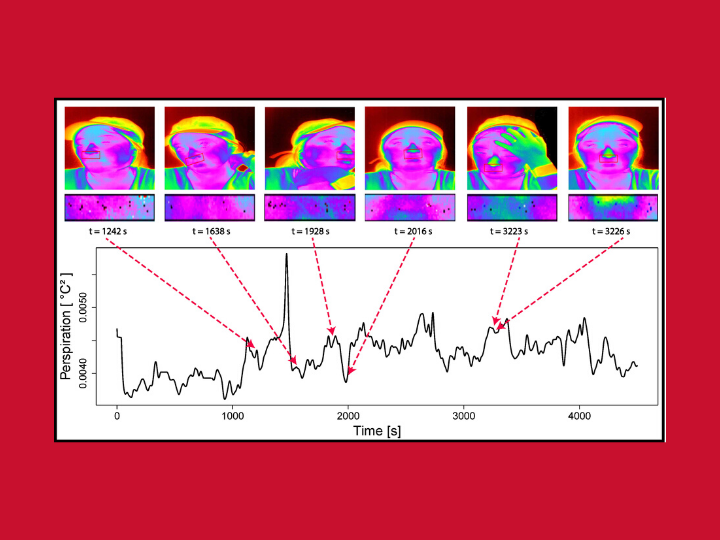

- Minute fluctuation of facial sweating emerges as the best way to measure stress during knowledge production and handling.

- Presenting views and findings to management is far more stressful than producing them.

- Given more relaxed deadlines, many office workers do not write longer reports but spend all the extra time to style them better.

- Spell checkers – despite their bad rap in the context of texting - save the day in long writings, which would be riddled with mechanics errors in their absence.

“When you are stressed, you don’t realize this, but you perspire small amounts of from your nose. The more you are stressed, the more you sweat,” said Pavlidis, Eckhard-Pfeiffer Professor of Computer Science in the UH College of Natural Science and Mathematics, whose focus is human-computer interaction. “We also found people who have neurotic tendencies work better when they are regularly distracted by emails and the highly-educated worker relies too much on computerized tools such as spellcheck.”

Sixty-three study participants carried out a series of typical tasks and office activities including writing essays, taking breaks and presenting their findings before their managers. Half of the participants wrote their essays while being regularly distracted by emails while the other half received their emails in batches. This study is the first of a series of studies on knowledge work funded by a $1.2 million grant from the National Science Foundation.

A thermal facial camera tracked perspiration levels around the nose and upper mouth while wearable devices on the chest and wrist monitored heart and breathing rates. Two cameras one on the computer screen and the other tucked in the ceiling – recorded participants’ facial expressions and hand activities.

“This study was a comprehensive microcosm of all things happening in a 21st century office,” Pavlidis explained. “Crowdsourced data analysis is expected to lead to personalized recommendations for handling email interruptions and a deeper understanding of how people cope with different office activities. If the initial analysis we did is an indicator, the conclusion is that people who work at the office in knowledge professions have far more diverse responses than people in other professions we studied in the past.”