Sanghyuk Chung and Graduate Student Led Study Published in Molecular Cancer Research Journal

Researchers at UH’s Center for Nuclear Receptors and Cell Signaling have furthered the cancer research community’s understanding of cervical cancer causes and treatment in a new publication.

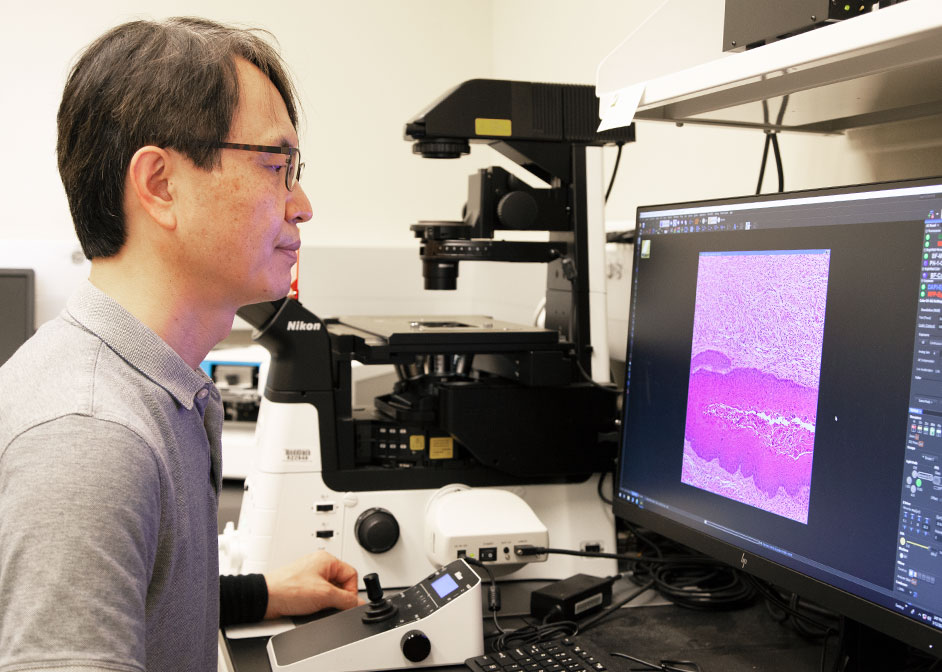

Associate professor of biology and biochemistry at the University of Houston, Sanghyuk Chung, and his former Ph.D. student Yuri Park, led a study to investigate the progesterone receptor’s role in the development of cervical cancer.

Their findings were published in the American Association for Cancer Research’s Molecular Cancer Research journal and were featured as an “Editor’s Pick”.

They found the progesterone receptor gene expression is reduced in cervical cancer, and their findings suggest that reactivation of this gene’s expression may improve the survival rate of patients with the cancer.

“Our study could possibly be used as a prognostic factor or biomarker to help physicians decide whether a woman who has pre-cancerous legions needs to be treated,” said Chung, a member of UH’s College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics. “If we know who will progress and who will not, then we can avoid unnecessary treatment.”

Park, who is now a postdoctoral associate in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology at Baylor College of Medicine, spent four years on the study at UH.

“I am so grateful the paper was published in Molecular Cancer Research and selected as a highlight of the issue,” said Park. “I personally think that cervical cancer mortality rates are underestimated. As a young scientist, I hope this study can increase awareness and ultimately save lives.”

Progesterone Receptor Correlation to Cervical Cancer Development

Chung explains that more than a decade ago, a research group with the World Health Organization carried out a study on human papilloma virus (HPV)-infected women and divided them into two groups: oral contraceptive users and nonusers. They found in the HPV-infected population, if a woman uses an oral contraceptive for more than 5 years, they have about double the risk of getting cervical cancer.

“That was probably the strongest evidence that female hormones may play a role,” said Chung. “Those oral contraceptives typically have estrogen and progesterone in different ratios.”

Using female mice engineered to express HPV oncogenes for the study, researchers tracked the hormonal fluctuations of the mice’s reproductive cycles, looking at the normal rise and fall of estrogen and progesterone.

They hormonally treated the mice with additional estrogen in order to promote cancer development but further investigated why the hormone was needed to promote the disease.

“When estrogen is high, progesterone is not produced much,” said Chung. “Estrogen must decrease for progesterone to increase, which is the norm in both mice and women. So we thought, if that’s the case, what if we can suppress the progesterone hormone instead and not treat the mice with estrogen? Will those mice develop cervical cancer?”

The group began studying mice that do not express the progesterone receptor, which is the protein needed for the progesterone hormone to work. In these mice, estrogen would rise, promote cancer, then progesterone would rise, but it could not prevent or reverse the estrogen effect because the progesterone receptor was missing.

“We tracked the HPV gene-expressing mice for about 10 months to see if they developed cancer,” he adds. “When the progesterone receptor was missing, that’s exactly what happened to the mice, they developed cervical cancer without the estrogen hormone treatment.”

Chung and Park also found the progesterone receptor to be haploinsufficient, meaning when one of the two copies of the progesterone receptor gene was removed, the mice were equally susceptible to cancer; having one copy of the gene was not enough to prevent cancer.

In their study’s conclusion, the group writes further in-vivo studies are needed to better understand the mechanism of progesterone during cervical cancer formation, “and our mouse model provides a valuable tool for such studies.”

All researchers on the publication are from UH’s College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics. In addition to Chung and Park, they include postdoctoral researcher Seunghan Baik, doctoral student Charles Ho and associate professor of biology and biochemistry Chin-Yo Lin.

Their study was funded by a grant from the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas, a National Institutes of Health grant and a University of Houston Large Core Equipment grant.

- Rebeca Trejo, College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics