News and Events

Black Deaf women exemplify perseverance and achievement

Panelists share stories of battling discrimination and isolation in the American South

Panelist Mary van Manen (left) tells of the discrimination and isolation she experienced growing up in Mississippi, while panelist Mary Perrodin pays close attention to the story unfolding from van Manen’s fingertips.

Interpreter Terra Jackson working hard to keep up with the two panelists who shared their stories in speech and sign language

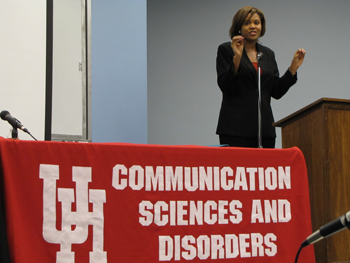

Event coordinator and panel moderator Sharon Hill, an adjunct lecturer on sign language interpretation

Growing up in the American South as a Black girl and coming of age during the Civil Rights Movement exposed Mary Lynch van Manen to daily discrimination.

She and her six sisters attended poorly-funded segregated schools in their native Natchez, Miss. and had infrequent access to medical care.

But she was more isolated than her peers while living under Jim Crow laws and customs because she and two of her sisters were born unable to hear.

"I was five years old when I left my family to go to the Mississippi School for the Negro Deaf in Jackson, Miss.," van Manen signed. "It wasn't until I was older that I realized the school didn't have any books."

Van Manen's story of battling the school administration to get books into the school — and finally receiving dirty, marked up books with missing pages that were castoffs from a Whites-only school — was just one of the many "Untold Stories of Black Deaf Women" shared February 26 in a panel discussion of the same name.

The event was hosted by American Sign Language Interpreting Program of the Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders (ComD) and organized by adjunct lecturer Sharon G. Hill.

Van Manen was joined on the panel by Mary Perrodin and Rebbie Smith, who were also born Deaf, as well as Dr. Shirley Allen and Michelle Martin, who lost their hearing in their 20s.

"The panelists' lives span over a generation of change for the Black community and they each have broken down barriers in education and employment for all of the Deaf community," said Hill, who moderated the conversation. "Their pride in self, commitment to education, and dedication to self-improvement is most noteworthy."

Allen is the President of Houston Black Deaf Advocates. Van Manen, the first Black Deaf person to graduate from college in Mississippi, sat on the Texas Governing Board for the Texas School for the Deaf.

Perrodin serves as an educator of the Deaf at Barbara Jordan High School and is pursuing her second Master's degree in counseling at Prairie View A&M University.

Smith is a long-time employee at the Michael E. Debakey Veterans Administration Medical Center. Martin is the President of the United Methodist Committee for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing Ministries.

Dean John Roberts described the program as "groundbreaking in giving voice to an often marginalized and little understood cultural group in our society."

"Our neglect of the deaf experience means that we have failed to learn about some of the inspiring stories of individuals who have achieved great successes in various fields while overcoming odds that most of us can only imagine," he told the audience of about 150 people.

Dr. Allen told of being a senior year at Jarvis Christian College in Hawkins, Texas majoring in music and preparing for the most important piano recital of her academic career when she lost her hearing.

"I performed my senior recital without being able to hear," she said in her voice and with her hands. "And as soon as I finished, that night I left for Gallaudet University."

Gallaudet in Washington D.C. was founded in 1864 by an Act of Congress to provide higher education to deaf and hard of hearing students. Its charter was signed by President Abraham Lincoln.

When Allen arrived on campus, van Manen was a senior and an Olympic runner. But there were very few other Blacks there. It was a shock to Allen's system since she had never gone to school with White students and had overnight entered the world of the Deaf.

"I couldn't hear and I couldn't sign," she said. "I was looking for my own thing but I couldn't find it."

The first sign a fellow student taught Allen was for the racial epithet "we call the N-word now," she said. He wanted her to know when she was being insulted and to not take that kind of abuse from her fellow students or professors.

"The very next day someone called me that word and I fell out laughing," Allen said. "It wasn't funny — I just didn't know what to say."

"It's sad but the story she's telling is true," said van Manen, a witness to the incident.

Allen persevered and went on to become the first African-American Deaf woman to earn a doctoral degree.

In addition to discussing their struggles to get academic educations rather than the vocational training others wanted to push on them, the panelists also explored the difficulties they have being understood.

Just as in the spoken English language, there are many dialects and cultural influences in American Sign Language. The Black dialect in ASL has produced signs for "ghetto," "my bad," "that's tight," and "oh, no, he didn't."

But the Black dialect is under threat the panelists said because not enough interpreters are trained in it.

"It's White sign language that's taught in schools," van Manen said. "I encourage schools to teach Black Deaf signs and Black Deaf culture."

CLASS offers a Bachelor of Arts degree in American Sign Language Interpreting (ASLI) — the first four-year degree in this area offered in the state of Texas. The coursework exposes students to the complexity and cultural nuances of sign language and prepares graduates to sit for national and state certifications in American sign language interpreting.

"We are very excited about this new program," said Dr. Lynn Maher, ComD Department Chair, adding that the first cohort to graduate with a BA in sign language Interpreting will do so in 2012.

But the panelists said it should not just be the Deaf, their family members and people wanting to pursue careers in interpreting who should learn American Sign Language.

They said the definition of full literacy in the United States should be expanded to knowing the ASL alphabet.

"Everybody needs to be able to at least fingerspell," Allen said. "That's easy and everyone can learn it."

A video of the entire panel discussion will soon be available in the Women's Archive and Research Center managed by the Women's, Gender and Sexuality Studies Program. People interested in learning more about the ASLI program should contact Dr. Michael Bienenstock, ASLI Program Coordinator, at mbienenstock@uh.edu.

—Shannon Buggs