Opening Previously Closed Doors (1955-1980, Section 2)

In the first half of the twentieth century, African-American physicians faced many obstacles. Discrimination was pervasive across the country and particularly severe in the Jim Crow South. A limited number of medical schools accepted black applicants, and an even smaller number of hospitals accepted them for residencies in specialized fields. In the South, local medical societies, such as the Harris County Medical Society (HCMS) and the Texas Medical Association (TMA), also denied them membership. In turn, most predominantly white hospitals, including those in Houston, refused to extend them privileges.

In incremental steps, each of these barriers began to fall and some crumbled even before the Brown decision. Dr. Edith Irby Jones became the first African-American student admitted to the medical school at the University of Arkansas in 1948. One year later, Dr. Herman Barnett filled the same pioneering role at the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) in nearby Galveston, Texas. Between 1949 and 1955, another fourteen black men entered UTMB.

In 1949, native Houstonian Dr. Joseph Clayton Gathe graduated from Xavier University in New Orleans. Another Catholic university, St. Louis University, accepted Dr. Gathe as their first African-American medical student because the nuns at Xavier highly recommended him. Dr. Gathe appreciated the opportunities afforded by his medical education, but he likened his experience as the only black student in his class to being a “roach in a glass of milk.” 1 He graduated in 1953.

In 1946, the National Medical Fellowships incorporated as a private, nonprofit organization dedicated to improving health care for underserved communities by increasing minority representation in medicine and other fields. Despite its efforts and individual breakthroughs, the spaces in medical school available to African Americans remained relatively small. The number of black students accepted in medical school remained disproportionately lower than the percentage of African Americans in the general population. Meharry Medical College and Howard University College of Medicine still educated the overwhelming majority of the nation’s black doctors.

A 1953 report on medical schools in the United States sponsored by the Association of American Medical Colleges and the American Medical Association recognized that women, African Americans, and other minorities were underrepresented in the ranks of their students. However, in noting the absence of diversity at many schools, the report implicitly criticized Howard University and Meharry because their students were almost exclusively of one race, effectively ignoring the limited opportunities for blacks and the essential role those two institutions had long played in insuring the presence of African American physicians who cared for underserved segments of the U.S. population.

Post-graduate studies presented the next barrier, although there were some breakthroughs before the Brown decision in this area as well. For example, Dr. Robert Bacon, who later moved to Houston after his service in the army during the Korean War, began a residency in urology at Washington University Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri in 1949. Native Houstonian, Dr. Louis Robey, also completed his residency in St. Louis at the Homer G. Phillips Hospital, and in 1955, became the first African-American in Houston to specialize in general surgery. After his military service, Dr. Joseph Gathe went to this same St. Louis hospital for a surgical residency, and upon its completion in 1961, returned to Houston.

Washington University Hospital and Homer G. Phillips Hospital were just two of the few facilities that offered African Americans post-graduate studies. Others included Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, D.C. (which was affiliated with Howard University), Provident Hospital in Chicago, Kansas City General Hospital No. 2, Harlem Hospital in New York City, and Katy B. Reynolds Hospital in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, that historically offered African-Americans post-graduate studies.

In the 1950s, however, a few more residencies opened in Houston and around the nation at hospitals that previously excluded black doctors. Dr. John Madison, a graduate of Meharry Medical College, became the first African American accepted for a residency in internal medicine at the Baylor University College of Medicine in Houston. Dr. Edith Irby Jones followed him several years later, in 1959, as the second black doctor in the program. In 1956, Dr. Clarence Higgins became the first black physician accepted for a residency at Houston’s Jefferson Davis Hospital. He specialized in pediatrics and eventually became the Hospital’s director.

Other white hospitals in Houston moved more slowly to change their policies, particularly regarding the extension of privileges. Some hospitals’ by-laws, for example, tied privileges to membership in the local chapter of the American Medical Association. Before 1955, the TMA and the HCMS denied African American physicians admission. One of the major obstacles to joining these organizations was the required endorsement of two current members; local white doctors remained reluctant to provide references. African Americans in health care continued to participated in the Lone Star State Medical, Dental, and Pharmaceutical Association to promote continuing medical education and to enhance the treatment of blacks in the state. Established in 1886, it was only the second organization of its kind in the nation in the United States.

One year after the Brown decision, however, changes were afoot. The HCMS admitted its first African-American members, Dr. Thelma Patten Law and Dr. John Madison, in November 1955. Shortly thereafter, Dr. Walter J. Minor, Dr. Michael Banfield, and other black doctors also joined. A native of St. Paul, Minnesota, Dr. Minor established his practice in Houston in January 1932, but the HCMS had refused to admit him for more than 23 years. The TMA also began to accept African-American members in 1955.

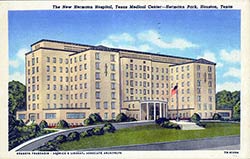

Despite membership in the local medical societies, many white hospitals in Houston continued to deny African American doctors privileges throughout the 1950s. Hospital boards often made the decision to keep their facilities segregated, and at other times, the medical staffs who voted on privileges, did so. The charter for Hermann Hospital explicitly limited its staff members to white males.

Citations

- “Joseph Clayton Gathe, Sr.” African-American News and Issues [on-line archives] (accessed 27 January 2005)