When George Díaz conducts research along the Texas border, he initially tells people he is researching business. It's only later they discover his real research interest: smuggling. A native of Laredo, Díaz is the new Visiting Scholar for the University of Houston Center for Mexican American Studies (CMAS). His research explores the history of smuggling along the Texas border.

"I grew up watching reports of drug violence and crime,but I also saw a lot of things with my own eyes, in terms of how common smuggling was," he said. "In truth, most smuggling is nonviolent, and I knew that was a story that wasn't in the news."

Since 1986 the CMAS Visiting Scholars Program has recruited experts, who may be interested in tenured or tenure-track positions, to generate research about the Latino community in such areas as history, art, sociology, psychology, anthropology, political science and English. The program allows the scholar to pursue his/her research and publication writings, and to develop a

spring semester class. Díaz is the program's 34th Visiting Scholar.

"Dr.Diaz' specialization is important and timely, given that the U.S-Mexico border has once again become very controversial," said Tatcho Mindiola, professor and CMAS director. "It is essential, therefore, that the University of Houston have an expert who can help students, as well as other scholars, understand the contemporary situation on the border within a historical context."

Díaz investigates what he calls a "hidden history" of smuggling along the border, beginning in 1848 through the present day.

"I'm talking about a social history of smuggling, how petty it is, how common it is and how normal it is," Díaz said. "I argue that there is a moral economy of smuggling, or a 'contrabandista' community, where some things are accepted and others are not."

Díaz notes that during the Mexican Revolution, when manythings were rationed, cotton, flour and sugar were among the items smuggled into Mexico - not to make money, but to meet basic needs. He says violence along the border related to smuggling heated up during the time of Prohibition in the 1920s, when liquor was smuggled from Mexico to the United States. These times

gave rise to a type of historical record he has found useful—the Mexican ballad or corrido. One such ballad details an encounter between a tequila runner, Leandro, and border authorities (Los Tequileros).

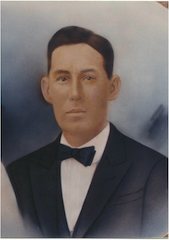

"I met a woman who was a sister of Leandro, and she shared photos of him," he said. " When you think of smugglers, you think of bearded men with guns and rifles, but I have an image of him on his wedding day when he's 18 years old. It's beautiful."

Díaz iscompleting a book about his research, "Contrabandista Communities, A History of Smuggling on the U.S./Mexico Border." Additionally, he is developing an upper-level class for the spring semester titled, "Smugglers, Saints and 'Aliens' in the U.S. – Mexico Borderlands."

"Smuggling is a natural response to laws," he said. "Border people are not criminal, but national laws push criminal activity to the borderlands."

For more information about theCMAS Visiting Scholar Program, visit http://www.class.uh.edu/CMAS/