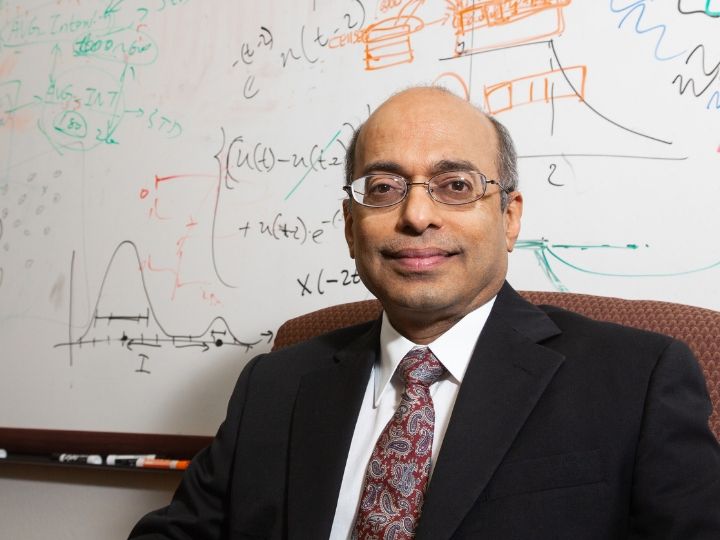

Badri Roysam, chair of the University of Houston Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, is leading a $3.19 million project to create new technology that could provide an unprecedented look at the injured brain. The technology is a marriage, as Roysam calls it, between a new generation of “super microscopes,” that deliver detailed multi-spectral images of brain tissue, and the UH supercomputer at the HPE Data Science Institute, which interprets the data.

“By allowing us to see the effects of the injury, treatments and the body’s own healing processes at once, the combination offers unprecedented potential to accelerate investigation and development of next-generation treatments for brain pathologies,” said Roysam, co-principal investigator with John Redell, assistant professor, McGovern Medical School at UT Health. Funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), the project also includes NINDS scientist Dragan Maric and UH professors Hien Van Nguyen and Saurabh Prasad.

The team is tackling the seemingly familiar concussion, suffered globally by an estimated 42 million people. This mild traumatic brain injury, usually caused by a bump, blow, or jolt to the head, disrupts normal brain function, setting off a cascading series of molecular and cellular alterations that can result in neurological, cognitive and behavioral changes. Concussions have long confounded scientists who face technological limitations that hinder a more comprehensive understanding of the pathological changes triggered by concussion, causing an inability to design effective treatment regimens. Until now.

“We can now go in with eyes wide open whereas before we had only a very incomplete view with insufficient detail,” said Roysam. “The combinations of proteins we can now see are very informative. For each cell, they tell us what kind of brain cell it is, and what is going on with that cell.”

The impact is immediate

Injury to the brain causes immediate changes among all brain cells, severing some connections and potentially causing blood to leak into the brain — where blood is never supposed to be — by breaching the blood/brain barrier. After a concussion, the brain tissue becomes a complex “battleground,” said Roysam, with a mix of changes caused by the injury, secondary changes due to drug treatments, side effects and the body’s natural processes. Untangling these processes will allow the team to develop new medication “cocktails” of two or more drugs.

“We will present a carefully validated and broadly applicable toolkit with unprecedented potential to accelerate investigation and develop next-generation treatments for brain pathologies,” said Roysam.

Once validated, the new technology can also be applied to strokes, brain cancer and other degenerative diseases of the brain.