Part of ‘Galápagos Evolving’ Study Abroad Course

Sandy beaches. Blue skies. Tortoises. Iguanas. Finches. Hammerhead sharks.

Student working on project to study how increased nutrients affect algae growth.Nearly 600 miles off the coast of Ecuador lies the Galápagos archipelago. These islands, which are of volcanic origin, stretch out over several hundred miles, with microclimates ranging from arid desert terrain to tropical woodland.

Student working on project to study how increased nutrients affect algae growth.Nearly 600 miles off the coast of Ecuador lies the Galápagos archipelago. These islands, which are of volcanic origin, stretch out over several hundred miles, with microclimates ranging from arid desert terrain to tropical woodland.

The flora and fauna found on these islands played a key role in helping Charles Darwin shape his theory of evolution. The Galápagos is still home to a robust research community, with scientists continuing in Darwin’s footsteps.

Conducting Research on San Cristóbal Island

In May, 29 University of Houston students traveled to the Galápagos Islands as part of the College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics’ “Galápagos Evolving” course. They spent three weeks on San Cristóbal Island—the very place where Darwin first landed in the Galápagos in 1835—conducting research alongside scientists from the Universidad San Francisco de Quito.

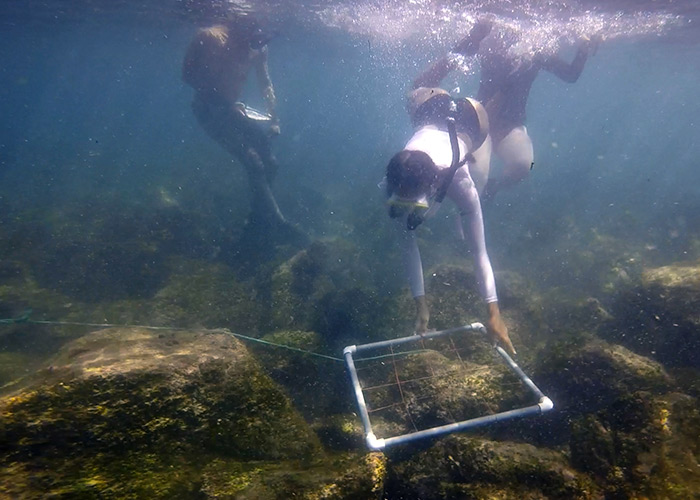

Student placing quadrat to count pencil urchin and algae density.This course, which is in its third year, was developed by Andrew Hamilton, NSM associate dean for student success, during his time as associate dean in the Honors College. The course was later expanded to include NSM faculty members Ricardo Azevedo, Ann Cheek and Tony Frankino, and Marc Hanke from the Honors College.

Student placing quadrat to count pencil urchin and algae density.This course, which is in its third year, was developed by Andrew Hamilton, NSM associate dean for student success, during his time as associate dean in the Honors College. The course was later expanded to include NSM faculty members Ricardo Azevedo, Ann Cheek and Tony Frankino, and Marc Hanke from the Honors College.

Before heading out on the research expedition, students spent a semester learning about the geology, biology, history and culture of the Galápagos.

Biology Textbook Come to Life

“Seeing the iguanas and tortoises and finches in the Galápagos, made me realize, ‘They’re real, they’re not just something in a biology textbook,’” said Amaryllis Fernandes, an honors biomedical sciences major who participated in the course. Of the 29 students in the course, 18 were from NSM.

While visiting the Galápagos, Darwin noticed that many of the species he saw were similar to those found on the South American mainland. After returning to England, he realized, with the help of the imminent ornithologist and illustrator John Gould, that many of the bird specimens he collected on the islands appeared nowhere else in the world. He also concluded that, despite his first impression, the birds he saw and collected did not all belong to the same species.

Students testing local samples in water quality lab.What Darwin eventually realized was that these finch species varied from island to island. Some finch species had long beaks while others had deep beaks, depending on their food sources and other factors. This observation was one of the key pieces of evidence that helped him shape his theory of evolution.

Students testing local samples in water quality lab.What Darwin eventually realized was that these finch species varied from island to island. Some finch species had long beaks while others had deep beaks, depending on their food sources and other factors. This observation was one of the key pieces of evidence that helped him shape his theory of evolution.

“The finches, they’re fascinating, but if you went to the Galápagos without knowing the context, you’d say, ‘Really, Darwin, you chose the finches? Not the turtles, not the tortoises, not the iguanas, but the finches, the little brown birds?” said Matthew Barr (’16), a post-baccalaureate student in biology.

Research projects included understanding how algae, which serves as a food source for species such as sea urchins, marine iguanas, fish and sea turtles, shapes the environment, as well as understanding the impact of humans on the island.

With the beach only a short walk away from the research station, students spent their time cataloging algae density, sea urchins, sea lions and fish. Meanwhile, students lived with host families, sharing meal-times together, with one day of the week reserved as a family day.

Observing a Sea Lion Dissection

One of the projects investigated whether parvovirus, which normally infects dogs, has made the jump to the local sea lion population. Students on this project assisted the lead scientist by counting the sea lion and dog populations on the island.

One morning, a group of students were in for a surprise. As they returned from counting the sea lions on a nearby beach, they noticed one rolling around in the surf. Upon closer inspection, it turned out the sea lion was dead.

Concerned that the sea lion may have died from a parvovirus infection, the lead scientist authorized a dissection in order to determine the cause of death. In a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, the students got to observe.

“This is biology you don’t see very often,” said Barr, who was one of the students to discover the dead sea lion. “For example, their muscle tissue is very dark because they have lots of myoglobin, so they can hold more oxygen and stay submerged underwater longer.”

As it turned out, the sea lion died from a shark wound and secondary infection, rather than the feared parvovirus.

Final Project Chronicles Experience

After returning from the Galápagos, the students wrapped up with their final project, chronicling an aspect of their experience. Some presented scientific results, while others offered photo portfolios, podcasts, or video projects.

“I would recommend to students interested in this experience to be prepared to live a different style of life,” Barr said. “You’re going to sweat, you’re going to take cold showers, you’re going to walk a lot, and you’re going to work hard.”

- Rachel Fairbank, College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics