Today, an American ceremony of innocence. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Issues of the 1916 American Review of Reviews reveal a strange view of war. The last Indian Wars and the Spanish-American War had not brought horror home to most Americans. The Civil War certainly had, but it was now a recollection of a previous generation. Most people remembered its heroics far more clearly than its agony and blood.

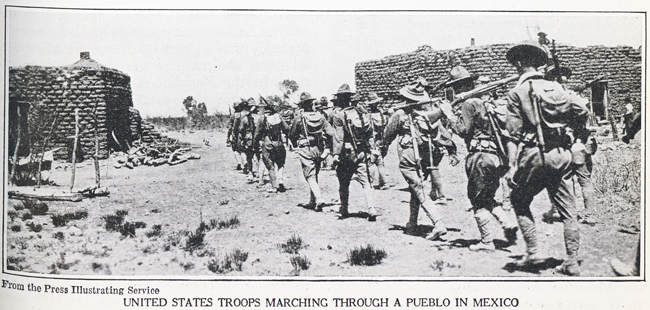

By now, WW-I had settled into a trench war of attrition in Europe; but it'd be another year before we joined that fight. At the moment, the magazine shows as much interest in our Mexican border scrap with Pancho Villa as the war in Europe.

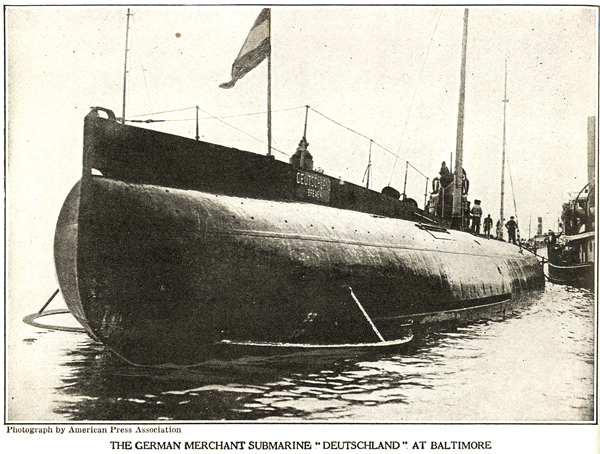

The British liner Lusitania had already been sunk by a German submarine, killing 1200 civilians -- many of them American. Yet the very first article celebrates the arrival of the German submarine Deutschland in Baltimore. This civilian merchant submarine had dodged the Allied blockade. It brought in expensive chemical dyes for sale to the US, and went back with a load of badly needed nickel and rubber. The article calls it a wonderboat and says that more like her are coming. But the German Navy took the Deutschland over after one more merchant trip. No more peace and good will -- she now set about to sink thirty or so allied ships.

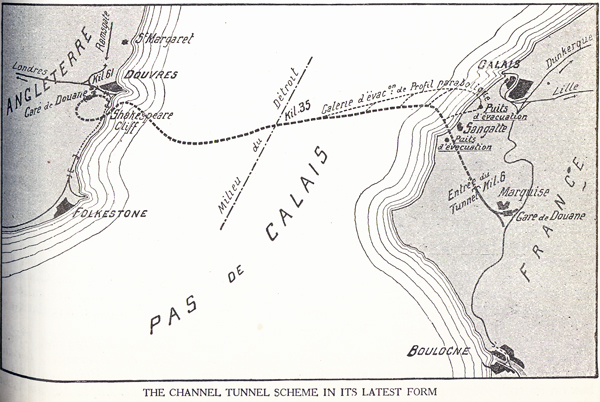

To get here and back, that submarine had slipped through the contested waters of the English Channel. Another article laments Britain's and France's failure, after a century of talking about it, to drill a tunnel under the Channel. Seventy-eight years and another World War would pass before the Chunnel was finished.

The magazine paints war and its technologies as interesting. Several articles are about military training in different countries. They tell about all the far flung combatants -- Turks, Romanians, Russians, Italians -- about German East Africa and Arabia. We read about leaders and alliances. Yet we are not shown the worst of it in the ghastly trenches of Ypres and the Somme.

Instead, echoes of our Civil War punctuate current events. One article seems to sum it up. It's about sculptor Henry Shrady, just finishing a memorial to General Ulysses S. Grant in front of the US Capital. Many of us have walked by it: Grant sits on his horse flanked by two huge bronze scenes of war.

One is a cavalry group charging into battle, the other, an artillery unit careening down a muddy road. Brilliant action pieces, worthy of Remington -- all the urgency of the moment! Yet the article points to the key omission. It says, "[Shrady] eliminated all suggestion of the gruesome incidents of war -- no man or horse is dying; no blood is flowing; no agony is visible."

That was 1916. Three years later, our own soldiers came home (if they came home) -- many with missing limbs, eyes vacant, lungs ruined by chlorine gas. And William Butler Yeats saw quite clearly what'd happened. For that is when he wrote,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

The American Review of Reviews. (Albert Shaw ed.) Vol. 54, July-Dec., 1916

William Butler Yeats' complete poem, The Second Coming, from which I've quoted two lines, may be read in its entirely online on the Poem of the Week site.

Engravings from the Review of Reviews. Grant Memorial photos below by J. Lienhard.