Changes in Medicine (1927-1954, Section 8)

The 1940s represented a time of dramatic changes in medicine. World War II, had revealed the advantages of certain antibiotics against infections that long plagued humans and often resulted in amputations or death. Gerhard Domagk, a German pathologist and bacteriologist, had developed sulfa drugs in the mid-1930s, and received the 1939 Noble Prize in Medicine.

Sulfa drugs “began to be prescribed in vast quantities: by 1941, 1700 tons were given to ten million Americans.” 1 Sulfa drugs provided effective treatment of bacterial infections, such as streptococcus and pneumonia. Rather then killing invading bacteria, “they work rather slowly by arresting reproduction, thus counting on the body’s defenses to overwhelm the invading microbes.” 2 For all their effectiveness for certain conditions, however, sulfa drugs were highly toxic and thus researchers continued to seek other solutions.

In 1928, Alexander Fleming accidentally discovered a mold that destroyed bacteria in a Petri dish. It took fifteen years before the antibiotic that became known as penicillin was mass produced. Its use in World War II proved its effectiveness. Penicillin offered a less toxic alternative to sulfa drugs and acted across a broader spectrum of infections.

Fleming’s successful research further stimulated efforts to find more soil molds with anti-bacterial properties. The mass production of penicillin, new anti-malarial drugs, and the new anti-tuberculosis drug (streptomycin) initially heralded a new era in highly efficacious chemotherapy and the eradication of the world’s infectious diseases, although drug-resistant variants emerged as early as the 1940s. The federal government invested huge amounts of money in the mass screening and mass producing of these drugs. This research, thus, drew the government, academic science, and drug companies into a partnership in the 1940s that remains central to the structure of medicine in the United States today.

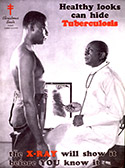

Vaccines and antibiotics became more effective and found greater distribution across the country. Consequently, tuberculosis, pneumonia, and other infectious diseases were no longer were the primary causes of death. Life expectancies increased for both white and black Americans.

Another significant change in the practice of medicine was the increased specialization. Dr. Derrick T. Vail, an ophthalmologist, first proposed the idea of a specialty board in 1908, and nine years later ophthalmology became the first one. The next three boards were in Otolaryngology (1924), Obstetrics and Gynecology (1930), and Dermatology and Syphilology (1934). By 1948, there were 18 specialties that offered board certification. In addition to completion of a residency in the particular specialty, board certification required passing both written and practical tests to verify a physician’s knowledge of the field.

The rise of specialists in the interwar period was not inevitable, and indeed, many generalists contested the trend. The laboratory revolution of the late 19th and early 20th centuries had greatly expanded scientific medicine, allowing individuals to carve niches in the medical marketplace by claiming special knowledge in (and thus authority over) some new area of medicine. Specialists also claimed new technologies, such as ophthalmoscopes in the late 19th century or x-rays in the early 20th century, to bolster their status. Specialists usually accessed these technologies at hospitals, which in the interwar years, worked to establish themselves as the center of medical care.

More effective anesthesia and antiseptic and aseptic procedures had allowed surgeons to open the abdomen with considerably less risk. These developments generated a localization of practice in surgery, or a geography of the body, reflected in surgical specialties such as urology, otolaryngology, or gynecology, for example. Surgeons, in particular, aggressively promoted the place of the hospital in American medicine to support their specialization through the provision of facilities, referrals from general practitioners, and training and research opportunities.

World War II reinforced the growing respect that physicians had gained since the beginning of the twentieth century. They used this authority to market their expertise and to control the provision of health care in partnership with hospitals. Most physicians maintained their own practices rather than working as employees of hospitals. They set their own fees, maintained their own schedules, and made their own decisions, often passing on the higher costs of new medical technologies to the hospitals and patients. Although segregation had forced most African Americans to work in an autonomous black hospital system, they similarly maintained separate practices.

As discussed above, before 1950, few African-American physicians joined residency programs because of the small number of facilities willing to admit them. One who did get a chance was Dr. Robert Bacon. In his rotation in urology during his internship at Chicago’s Provident Hospital, Dr. Bacon worked with physicians who granted him significant hands-on experience. He was accepted for a residency in urology at Washington University Hospital in St. Louis where he worked with equally engaging mentors. Dr. Bacon “found out that urology was something of an exciting field.” 3

Dr. Bacon passed most sections of his boards, but like many other physicians, needed to repeat one part. He worked with Dr. Wallace, a white doctor at Baylor, to prepare and then traveled to New Orleans to retake the pathology section at an all-white medical clinic. Recalling the awkward stares he encountered from the members of the clinic’s medical staff when he dined in the cafeteria with his examiner after the test, Dr. Bacon says that he did not even appreciate the magnitude of passing his boards until later. “And that thing didn't strike me until we were about halfway back to Houston at about 10,000 feet - oh my God, I passed the board! It was such a delayed reaction. It hit me, I have passed the board. I am now a diplomat of the American Board of Urology.” 4